The following is from Karl Rove‘s opinion piece in this morning’s Wall Street Journal (emphasis mine):

“So what’s a president to do when the promises he made about his economic stimulus program fail to materialize? If you’re Barack Obama, you redefine your goals and act as if America won’t remember what you said originally.”

Anyone who remembers the ex ante and ex post justifications for the Iraq war may appreciate the irony.

Current Events, Economics, Private Equity, Uncategorized / No Comments

Brad DeLong, in his “Fair, Balanced, Reality-Based, and More than Two-Handed” blog recently posted a couple of charts to buttress his contention that, “employment losses are about to be bigger than in any previous recession since the Great Depression itself”.

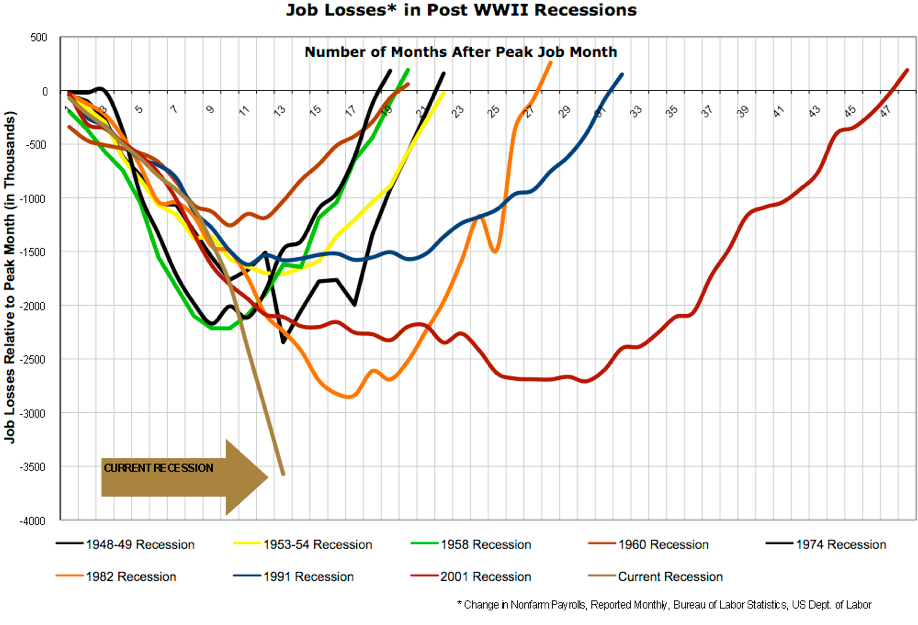

The more alarming chart is taken from Nancy Pelosi’s office wall:

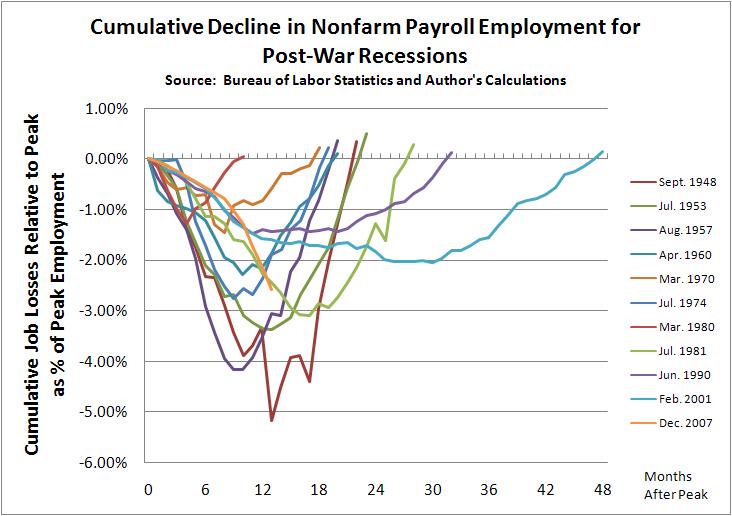

A naive observer might conclude that the current recession is the worst since WWII. Unfortunately this chart doesn’t adjust for the dramatic overall expansion of the labor force over the last fifty odd years. William J. Polley has produced a more informative (less ludicrously tendencious) percentage based comparison. Note that the current recession actually falls somewhere in the middle of the pack for post WWII recessions.

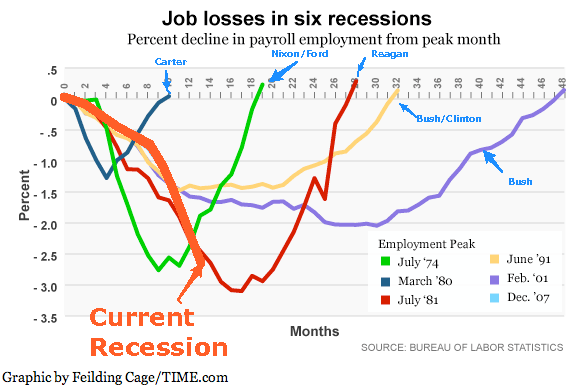

The second chart is an annotated copy of the Time Magazine original.

There is nothing actually wrong with the chart. However, the annotations are interesting. Mr DeLong has added the names of the Presidents who happened to be in office during the charted recessions. It isn’t clear what Mr DeLong’s purpose in doing this was exactly. Perhaps Mr DeLong is trying to suggest responsibility. If so, he appears to have made the classic mistake of confusing correlation with causation.

The other questionable addition is the gratuitous highlighting of the current recession. Painting something bright red and labelling it with a honking a great sign is not exactly the strategy of someone seeking to make a sober analysis. Perhaps the real purpose of this overdone annotation is to conceal the fact that, when charted in relative terms, the trajectory of employment in the current recession looks a lot like that of the 1981 recession. While certainly very unpleasant, the 1981 recession did not in fact result in the end of civilization, which is not the kind of thing you want to dwell on if you are trying to sell people on your, “the world is going to end if Congress doesn’t spend” view of the world.

As the stimulus package wends its way through Congress the arguments in support of even the basic principle are becoming increasingly half-hearted. Brad Setser has compared the current recession with other post 1945 downturns and come to the conclusion that it is really, really bad. He thus endorses a large stimulus:

“That is why — despite the risks — I support a large stimulus. The United States debt levels suggest that it still has room to use the public sector’s balance sheet to try smooth the economic cycle. And there is nothing moderate about the current cycle.”

‘Things are really bad, we should try something, even if its very risky’, isn’t exactly a ringing endorsement of fiscal stimulus as a response to the current crisis. In fact, it reveals the biggest problem with fiscal stimulus. While the costs are large and certain, the supposed benefits aren’t exactly guaranteed.

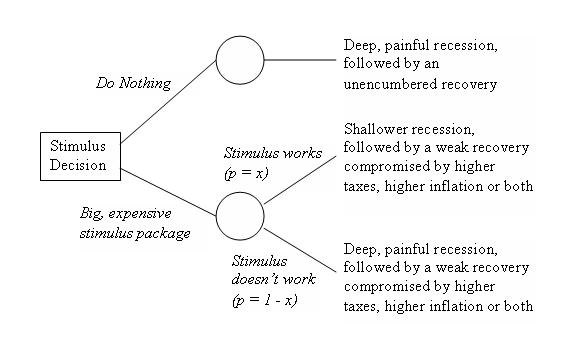

In situations like this it is often helpful to lay out the options and their consequences in the form of a decision tree:

In this case X is certainly less than one. It may in fact be significantly less than one.

At the very least, this should give us pause before endorsing stimulus as a policy response. It is always worth remembering that there is no situation so bad that Congress can’t make it worse.

Atlantic blogger Megan McCardle doesn’t think much of the the ongoing discussion about whether or not the next President should meet with controversial foreign leaders.

To date, the current administration has been pretty resolute in its policy of not talking to people it doesn’t like. This could reasonably be described as the angry two-year-old approach to foreign policy.

Unsurprisingly, the lack of invitations to the White House has not had a huge impact on the policies of Iran, Venezuela or North Korea.

To be fair, the President’s lack of involvement has little to do with the administration’s difficulties in dealing with the country’s various foreign antagonists. The fact is, getting unfriendly regimes to do what you want is largely a question of leverage. For various reasons, the US doesn’t have any.

Going further, the administration’s no talking policy isn’t quite as pigheadedly stupid as it sounds. A meeting with the President can be a significant carrot. It’s the kind of thing that you might reasonably want to hold back until the final stages of negotiation.

More importantly high level talks with dictatorships can be dangerous for the President. In any high profile meeting the administration tends to be under enormous pressure to show results. Dictators, who don’t have answer to voters or the press, have no such concern. The playing field is thus not level, which can easily result in the good guys making concessions that they probably shouldn’t.

However, this is a concern that can easily be addressed. We have tended to get very hung up on whether or not the President should speak to problematic foreign leaders. What really matters is what the President would say. Obama could largely eliminate concerns about his engagement policy by addressing the issue along the following lines:

“Would I speak with President Ahmadinejad? Certainly. Communicating with foreign leaders is part of the President’s job. Would President Ahmadinejad enjoy the conversation? Probably not. I would tell him in no uncertain terms that his country is on a dangerous path that could lead to conflict with the United States.

We should have no illusions that my words alone will change the policies of the Iranian government. However high level engagement is one of the tools we have at our disposal. I will not neglect any opportunity to communicate our views and apply pressure to the Iranian regime. This is one of those times we need a full court press.”

Current Events, Economics, US Politics / No Comments

Harvard economist Greg Mankiw supports the “plague on both your houses” view of Congress’ role in the Freddie & Fannie fiasco.

Current Events, Economics, US Politics / No Comments

Events are moving so quickly that this post is already two massive bailouts behind the times. However, the quasi-nationalization of Freddie and Fannie is such a significant event in the history of finance and government that it bares belated comment.

One of the (many) great tragedies of the Bush administration is that its reputation for untrustworthiness, incompetence, and blatant political hackery became so overpowering that people stopped listening. So on the rare occasions when the administration displayed the foresight so conspicuously lacking in Iraq and New Orleans, nobody listened.

The Bush administration repeatedly warned that Freddie Mac and Fannie May were dangers to the stability of the financial system. Congress, determined to show that the administration doesn’t have a monopoly on self righteous, arrogant bungling, and always mindful of the flow of campaign contributions, chose not to listen. The result is that taxpayers are on the hook for Freddie and Fannie’s losses.

Congress has (shamefully) shown itself to be not so very different from the administration. When it came to Freddie and Fannie, Congress chose to believe what was personally and politically convenient, regardless of the evidence. Faced with a crisis, Congress reached for the quick fix solution of having Freddie and Fannie expand their operations, without considering the risk. Ignoring outside advice they took their cue from lobbyists who wanted to use the housing crisis to help Freddie and Fannie escape the restrictions imposed as a result of their respective accounting scandals.

Finally, Congress appears to be dead set on learning nothing from the experience. The political groundwork is already being laid for the resurrection of Fannie and Freddie. No doubt bigger, more political and even less transparent than before.

Perhaps the most depressing aspect of this whole sad saga is that it really deosn’t seem to matter much who controls Congress. Between 2002 and 2006 the Bush administration and the Republican Congress put on a master class in bad government. Sadly, it appears from their recent performance that congressional Democrats were taking notes.

It appears that poor loser Boeing is going to appeal the Air Force’s decision to buy Northrop Grumman/Airbus tankers on the grounds that choosing the winner based on which proposal gave the best value for taxpayer money was patently unfair.

Whatever spurious reasons Boeing actually comes up with for challenging the contract, the real issue is whether the Air Force can weather the political storm it’s decision has created. The key concerns are jobs, the award of a lucrative contract to a foreign company and national security. All these concerns will receive plenty of air time, but none have any real foundation.

Perhaps the most ridiculous claim to date is that the decision will somehow cost thousands of American jobs. Both Boeing and Airbus have global supply chains with a high degree of overlap. US suppliers, who are barely keeping up with with demand for parts for civilian planes, may see a small decline in future orders from Boeing, which will likely be offset by increased orders from Airbus.

Boeing itself will have to shut down it’s 767 production line sooner than it might like. However this will only be a pause for retooling. The company currently has an epic backlog of civilian aircraft orders, which means that there is precisely zero chance of layoffs.

You could argue that Boeing might have hired more people in the future had it won. Of course these hypothetical jobs are balanced by the actual hiring Northrop Grumman will be doing in Alabama, where the Airbus tankers are to be assembled.

The national preference and national security concerns are only marginally less idiotic. EADS (the corporate parent of Airbus) is a joint French/German company. France and Germany are of course close NATO allies, who already have access to any military secrets likely to be involved in what is essentially a flying fuel truck.

If anything, the Airbus tanker represents a major opportunity to strengthen trans-Atlantic military co-operation. Committing to a partly European tanker is an obviously friendly gesture, which may will be reciprocated in the form of better access to the European market for US military suppliers. Over the long run, a reduction in irrational national preference biases in arms purchases would increase supplier competition and decrease costs for all NATO countries. In addition, it would likely result in greater commonality of equipment, and thus greater interoperability, amongst NATO forces.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the whole situation is that Air Force has demonstrated the ability to make a purchasing decision based solely on military considerations. This will, assuming the decision is allowed to stand, have a very salubrious effect on future acquisition contests. If suppliers get the idea that their efforts are best spent on engineering rather than lobbying, the result will be a military that is both better equipped and much less expensive.

The only real losers will be Boeing shareholders. Right from the start, Boeing’s tanker proposal was basically a scam designed to keep the obsolete 767 in production. This would have been a fabulous deal for Boeing. The development and tooling costs for the 767 were paid off long ago, so every additional 767 sold would have had a very pleasing effect on the bottom line.

While I’m sure Boeing stockholders are rooting for the Airbus deal to be overturned, such an outcome would be a travesty of justice and a gross insult to common sense. Still, this is an election year, so anything is possible.

In contrast to the previous post, from time to time data emerges that illustrates how wealthy New Zealand is in ways that are not really captured by GDP. The fascinating book Microtrends contains the following, very encouraging, observation:

“And who gets the most sleep? New Zealanders and Australians, where 28 and 31 percent, respectively, get more than nine hours of sleep a night.”

By contrast, the average American apparently sleeps less than seven hours a night, while four out of ten Japanese sleep less than six hours a night. Inspired by this evidence of cultural superiority I think I will take a relaxing mid-morning nap.

One of the things that has always struck me about the US is what a spectacularly wealthy country it is. Or alternatively, how pathetically poor New Zealand is by comparison. Occasionally data crops up that depressingly reinforces this impression.

The cunning cartographers responsible for this map of the US have replaced the name of each state with the name of a country that generates similar GDP.

Embarrassingly, it turns out that New Zealand’s GDP roughly approximates that of Washington DC (population 580,000, area 177 square km).